The chronicle

Do You Want to Catch Up With Chronicles 2025?

How About Catching Up With Chronicles before 2024?

How About Catching Up With Chronicles before 2024?

How About Catching Up With Chronicles before 2024?

How About Catching Up With Chronicles before 2024?

How About Catching Up With Chronicles before 2024?

PARALLEL AVANT GARDES

Barcelona, 17th of February 2026

Between 1918 and 1939, Europe’s political fractures forced artists to choose between utopia and refuge: in the Soviet sphere, art was recruited to build a new world, while in Catalonia and Spain it often became a shelter for identity, memory, and survival. Paris—bohemian, porous, and fiercely international—became the key relay point where these languages of cubism, constructivism, and surrealism collided, conversed, and occasionally fused. This article traces those intersections and divergences, from émigré bridges like Olga Sacharoff to the charged symmetry of 1937, when the Soviet pavilion faced Spain’s Guernica.

Text by Angie Afifi

The interwar period of the last century was a time when the world was literally coming apart at the seams and art was trying to find new ways to breathe in this chaos. The First World War had just ended, the October Revolution had overturned Russia, then came the crash of 1929, fascism was gaining strength, and by the end of the decade the approach of another major war could already be felt. In this whirlwind the Soviet avant garde and Catalan and more broadly Spanish art from 1918 to 1939 developed in parallel, sometimes intersecting, sometimes pushing away from one another. Soviet artists often saw art as a tool for building a new world, while Catalan and Spanish artists frequently sought refuge in art. Some through new figuration, some through surrealism, some clung to tradition, and others broke with it completely. What is striking is that the most important link for all of them turned out to be Paris, a place where creative people gathered while escaping revolutions, dictatorships, and wars.

Imagine the roaring 1920s, when Paris became the true capital of the avant garde. Cheap living, freedom, cafés and bistros where people could argue for hours about form and color, literature, philosophy, and politics. After 1917 artists from what was the former Russian Empire such as Marc Chagall (1887-1985), Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979), Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962), Mikhail Larionov (1881-1964) and many others poured in. Some fled the Bolsheviks, others arrived simply to see what was happening in this incredible bohemian and free atmosphere. On the other side were Spaniards and Catalans such as Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Joan Miró (1893-1983), Juan Gris (1887-1927). Later came those escaping Primo de Rivera and then the Civil War of 1936 to 1939. Imagine sitting in the famous café La Rotonde in Montparnasse, where all the artists of that time gathered. You could sit for hours with a cup of coffee, watch someone sketch on a napkin, overhear conversations at neighbouring tables, discuss new exhibitions. Ideas were simply in the air and even if you never spoke personally with Picasso or Chagall you still absorbed them through this shared atmosphere. Take the 1937 World Exhibition in Paris. The Soviet pavilion with its constructivist works stood opposite the Spanish one where Picasso’s tour de force ‘Guernica’ was hanging. Two antifascist statements standing side by side.

The Soviet avant-garde until around 1932, before it was crushed by socialist realism, was infused with the idea of radically remaking the world through art. Malevich called Black Square and suprematism as a whole the zero point of art, the moment when painting frees itself completely from depicting objects and conveys only pure feeling. Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953) and Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956) in constructivism insisted that art must be useful, for the masses, for industry. El Lissitzky (1890-1941) with his prouns built a bridge between painting and architecture. All of this was radically abstract, aimed at breaking the old world and erecting a new one. At the same time many of them looked toward Paris. Malevich saw the cubism of Picasso and Gris, Lissitzky worked with the Bauhaus and carried constructivist ideas across Europe.

As for Catalan art of that time, it was also full of complexity and contradictions, and the exhibition Figuraciones entre guerras 1914 to 1945 held at Sala Parés in Barcelona from December 4, 2025 to February 7, 2026 reflected this clearly. The exhibition gathered works that illustrated the tension between tradition and new approaches. On one side Noucentisme, a revival of Catalan culture, classical harmony, and national self awareness, and on the other modernism pushing toward experimentation, breaking old canons, and searching for entirely new forms.

Josep de Togores (1893-1970), the Russian Catalan Olga Sacharoff (1881-1967), Manolo Hugué (1872-1945), Joaquín Torres García (1874-1949), Juan Gris (1887-1927), Joaquim Sunyer (1874-1956) and many others searched for these new figurations, meaning fresh ways of depicting people, objects, and the surrounding world. They began with the influence of Cézanne, his approach to form through color and volume without rigid perspective, experimented with cubism where everything is broken into geometric facets and shown from several angles at once, and moved into surrealism, portraying figures as subconscious and fantastical. Some captured human drama, especially during the Civil War years, while others retreated into a poetic distance from reality.

Could these worlds really intersect. It turns out they could and quite vividly. Take Olga Sacharoff. Born in Tiflis, now Tbilisi, in the Russian Empire, she received her artistic education at the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts and emigrated to Barcelona in 1915. Her post impressionist figuration with cubist elements formed a direct bridge between the Russian school and the Catalan context. She literally introduced cubism into Catalan art and even during the Franco years received the Gold Medal of Barcelona in 1964. A classic migrant trajectory. Paris as a transit point, then adaptation to a new home.

Joan Miró, a Catalan, intersected in Paris not only with key surrealist figures such as André Breton (1896-1966) and Max Ernst (1891-1976) but also with Russian émigrés like Marc Chagall. His surrealism with organic almost biological forms was a reaction to chaos, an attempt to retreat into the subconscious as a refuge. Miró’s automatism resonates with the idea of liberating form often associated with the Soviet avant garde of that time, and his antifascist works such as Help Spain from 1937 also echo Soviet antifascism.

Joaquín Torres García is another voice that cannot be overlooked. Uruguayan by origin, he lived in Barcelona from 1891 to 1917. He developed universal constructivism, a style based on geometric forms and abstract structures that combined elements of Russian constructivism of the 1920s with a metaphysical and spiritual dimension characteristic of his work. His pictograms and abstract constructions can be seen as a synthesis of tradition and modernism filtered through the Parisian experience where he encountered both cubists and constructivists.

Another important artist whose works were shown at the Sala Parés exhibition was Juan Gris, a Spaniard who lived in Paris from 1906 and played a major role in the development of cubism. Gris was one of the brightest representatives of synthetic cubism, a phase when artists moved away from fragmenting form into separate pieces as in analytic cubism and began working with more unified compositions, often using ready made elements such as newspapers, scraps of paper, and textures, bringing collage into cubism. His work strongly influenced the later development of modernism including Salvador Dalí (1904-1989), Diego Rivera (1886-1957), Joseph Cornell (1903-1972), and pop artists such as Andy Warhol (1928-1987) and Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1997).

Yet what is most interesting is that despite all these intersections no single unified style emerged. Why did this happen. It seems that different contexts and origins played a decisive role. Each had their own tasks. The Soviet avant garde was utilitarian and utopian, while Catalan art often became escapist or nationally inflected, where the figure served as a way to preserve identity in chaos. Modernism in this sense became polyphonic. Cézanne acted as a shared ancestor, cubism provided a language for dismantling reality, and surrealism offered a language for diving into the subconscious. Paris undoubtedly intensified the exchange of ideas but did not erase differences. On the contrary it highlighted individuality and the choice of a personal artistic language, which itself became an act of resistance to circumstances and to the pressure of the surrounding world.

New York, 10th of February 2026

RECENT REDISCOVERY: ‘JUDITH ON RED SQUARE’

Vickery Art has recently rediscovered at auction in London an important work from Komar and Melamid’s legendary Nostalgic Socialist Realism Series, ‘Judith on Red Square’. Conceived and painted between 1983 and 1993, it is the first and only version for a large-scale painting which was never realized. Leading authority and author of a forthcoming monograph on Komar and Melamid, Dr Alla Rosenfeld writes about the painting, the story behind it and why it is relevant today.

Text by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D.

This significant work Judith on the Red Square (1993) was created by the influential Russian- American duo Vitaly Komar (b. 1943) and Alexander Melamid (b.1945), who collaborated from 1972 to 2003. Their oeuvre serves as a vital cross-cultural bridge in today’s international art market. Notably, they were the first Russian artists to receive a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (1982) and the first Russian artists to be invited to Documenta 8 in Kassel, Germany (1987).

Komar and Melamid’s work is held in prestigious permanent museum collections worldwide, including the Guggenheim Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, Museum of Modern Art; San Francisco Museum of Art; Victoria and Albert Museum (London); Stedelijk Museum (Amsterdam); Albertina (Vienna), and Museum Ludwig (Cologne).

After emigrating first to Israel in 1977 and then to New York in 1978, Komar and Melamid continued to refine the themes and strategies they had first explored in the Soviet Union. In the early 1980s, the duo began Nostalgic Socialist Realism, a series of 30 paintings designed to re-examine the Soviet experience. This series was vital in defining the New York phase of Sots Art. A part of this significant series is Judith on the Red Square, which offers the artists' personal interpretation of the tale of Judith beheading Holofernes.

In Nostalgic Socialist Realism the artists reflected their nostalgia for the lost fictional model of the world created by the Soviet system. As Komar and Melamid explained, in this series “three types of nostalgias merged: nostalgia for academic realistic painting, on which we were raised during the Stalin era; nostalgia for childhood and for what we saw in our childhood—and our childhood was spent under Stalin; and finally, nostalgia for Russian imperial grandeur, which for us was once embodied in the image of Stalin.”. Once characterized by a sharp irony toward Soviet life, Komar and Melamid’s Sots Art has evolved into an exploration of nostalgia and the nuances of historical memory.

In their painting Judith on the Red Square, Komar and Melamid employ an ironic deconstruction to subvert both an art historical icon of Judith and the heroic iconography central to Soviet official culture. The composition features a young girl (Judith), her face obscured, brandishing the severed head of Joseph Stalin. By transposing the biblical narrative of Judith and Holofernes into a Soviet context, the Russian-American duo reconfigures the Jewish heroine and the oppressive general into a contemporary political allegory representing the triumph of the citizenry over totalitarianism.

The work’s title and its central geometric motif of a square serve as a polysemic reference to Moscow’s Red Square, the historic and symbolic heart of the Russian capital. Flanked by the Kremlin walls, the square has historically functioned as a stage for the projection of state power, hosting events ranging from imperial coronations and public executions to the massive military parades intended to demonstrate Soviet hegemony. The artists further layer this reference by invoking the archaic Russian meaning of krasnyi, which originally signified "beautiful" rather than merely "red," thereby commenting on the square’s architectural and cultural prestige.

Beyond its geographical associations, the presence of the red square within the painting functions as a sophisticated art-historical dialectic. The geometric form directly evokes the non-objective aesthetic of Suprematism and the Russian avant-garde, placing these revolutionary art movements in direct visual tension with the figure of Stalin. This juxtaposition highlights the irreconcilable conflict between the radical abstraction of the early 20th century and the dogmatic, state-mandated aesthetic of Socialist Realism that eventually suppressed it.

From 1929 until his death in 1953, the image of Joseph Stalin served as the paramount symbolic nexus of Soviet propaganda, permeating every facet of artistic and cultural production. Representations of an omniscient Stalin were ubiquitous, manifesting in Socialist Realist painting, monumental architecture, banners, and ubiquitous posters. The symbolic construct of Stalin was intricate and multi-layered. He was deliberately engineered to embody the sacred and archetypal attributes of the Father of the nation, the wise Teacher, and the Savior of the land. Among these, the Father archetype emerged as one of the most robust and widely propagated images associated with his persona, establishing Stalin as the patriarch of all Soviet peoples.

This paternal image was reinforced by depicting the ideal Soviet child, from the mid-1930s onward, as unfailingly obedient and grateful. Socialist Realist paintings and propaganda posters frequently portrayed children in states of exultant joy, expressing profound appreciation for Stalin's fatherly benevolence. The ubiquitous slogan, “Thank you dear comrade Stalin for our happy childhood!” adorned entrances to nurseries, school walls, and the covers of magazines and books. The visual trope of the Leader paired with devoted children became one of the most significant and pervasive genres across the various media sustaining the cult of personality.

In their Nostalgic Socialist Realism series, Komar and Melamid turned to nostalgic motifs associated with their former model of the world, which was implanted in the minds of Soviet schoolchildren from a young age. Komar and Melamid, like all Soviet children, were taught that they “ live in the best country of the world, that Stalin is the greatest genius of humanity, a Father, a Teacher…”

Although several of Komar’s relatives fell victim to the Stalinist purges, his upbringing was nonetheless steeped in the state-mandated deification of the leader. Recalling his childhood, the artist noted: “After the divorce, my mother replaced my father’s portrait above my bed with one of Stalin. I was bedridden with the flu and a high fever at the time; looking up at that familiar face, the boundaries between reality and propaganda began to blur. All I could think of was the phrase we were always taught: "Stalin is our father!"

The artists reframed Stalinism through the lens of their own childhoods. As Vitaly Komar observed, “We created our own, individual Socialist Realism. In our consciousness and memory, May Day postcards and Ogonyok magazine illustrations merged with the somber masterpieces found in Soviet museums—works by Rembrandt, Caravaggio, and the Dutch, Spanish, and Italian masters.” This influence is evident in the Nostalgic Socialist Realism series; specifically, the harsh lighting in Judith on the Red Square evokes the dramatic chiaroscuro of Caravaggio or the intimate candlelight of French Baroque painter Georges de La Tour (1593-1652).

Following Stalin’s death in 1953, and especially subsequent to Nikita Khrushchev's landmark “Secret Speech” at the 20th Communist Party Congress in 1956, which officially denounced Stalin’s cult of personality and his criminal actions against the Soviet populace, a systematic process of de-Stalinization was initiated in Soviet Russia. Monuments dedicated to Stalin were demolished, portraits were relegated to specialized storage facilities, and his figure was even painstakingly excised from numerous popular group portraits, marking a decisive rupture with the pervasive iconographic tradition.

While adopting a pompous style reminiscent of Socialist Realist painting, Komar and Melamid’s Judith on the Red Square deconstructs the myth of the Soviet child as a figure of unwavering loyalty to Stalin. The work serves as a potent political commentary, reinterpreting a classic art-historical trope to critique the realities of Soviet life. By replacing Holofernes with Stalin, the artists transform Judith from a biblical heroine into a symbol of liberation from oppressive state power. Furthermore, her obscured face shifts the focus from an individual protagonist to the collective power of the anonymous masses, establishing Judith as a universal icon of resistance.

By addressing historical and political issues, the artistic duo shed light on topics that recently have become extraordinarily relevant again. These include the functioning of personal freedoms in a totalitarian state. A return of Stalin’s cult of personality is actively occurring in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, driven by a state-sponsored rehabilitation campaign and a desire to foster imperial nationalism and a strongman image.

ABOUT WHAT CANNOT BE COLLECTED

Barcelona, 3rd of February 2026

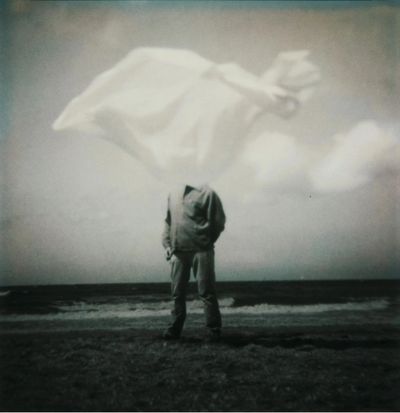

SThis January saw a staging of Marina Abramović’s seminal performance Balkan Erotic Epic at the Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona—a reminder of the enduring power of performance and action art to test the limits of the human body, belief, and endurance. It may be art which cannot be collected, however there are other ways that collectors can celebrate and remember the most powerful performances and actions by some of our greatest and bravest artists of today, through photographs, documents and videos.

Text by Angie Afifi

We often discuss the art market, its trends, prices, and major players. At its core, it is driven by the logic of possession. Usually, when we talk about the art market, the focus is on traditional forms such as painting, sculpture, drawing, and photography. Over time, new manifestations have joined them, including installations, digital art, and video art, forms that expand our habitual understanding of the art object. But what happens when art cannot be acquired or collected? When it is ephemeral, disappearing through time and space, and cannot be transferred onto a physical medium? Theatre, dance, and music, as long as they are not digitized or fixed in some way, remain outside the framework of the traditional art market. Performance art belongs precisely to this category.

If in art forms that presuppose the creation of a final object, its preservation, and its display, artists work with a variety of materials, then in ephemeral forms of art the human body itself becomes both the instrument and the artwork. Here the individual gives themselves entirely to the process, turning into living artistic material. Movement, breath, voice, presence all of this constitutes the final object, one that cannot be repeated or purchased.

In this sense, performance opens up a particular perspective. Art becomes not so much an object as an experience, an encounter, a moment that exists only here and now. It is precisely this ephemerality that makes it unique. But what if

It is no secret that art emerged together with humanity. Throughout history, artists have consistently turned toward the past, to its forms, symbols, and traditions. But what if one were to turn not only to the art of the past, but also to the very way of seeing and experiencing life, to rituals, to collective memory, to what lies hidden deep within us, in our bodies, our genes, the spiritual experience of our ancestors? Is such a contact with the inner history of the human being even possible?

It turns out that it is. Forms of art such as performance open hidden portals and propose new ways of perception and immersion. A central example here is the work of Marina Abramovic. Throughout her career, she has explored the boundaries of the physical and the spiritual, digging deeper than seems possible, moving toward the very beginning, toward origin and birth. Her Balkan Erotic Epic was first presented in England in 2025, and more recently, in January 2026, the work reached Spain, Barcelona.

According to the artist herself, this is her most ambitious project. The largest, you might think? Rather, the most vulnerable. Here the artist touches the most unprotected zone, the place where culture has not yet learned to pretend. And that is precisely why this project cannot be repeated. It is deeply connected to the artist’s own body, to her origins, to something that cannot be translated into a universal language.

In this work, Abramovic constructs a space in which archaic rituals, eroticism, and Balkan memory manifest through the body as a living archive. Memory exists here not so much in narrative as in gestures, breath, the reactions of the skin, in the way the body responds to fear, shame, and desire. Perhaps it is fear, shame, and desire that become the main driving forces of this life revealed in a work where pain and love coexist simultaneously.

What is also striking is that the performance process does not simply reproduce the past. It seems to awaken what is forbidden and repressed, yet painfully familiar. There is a sense that the body suddenly remembers what the mind has long tried to forget.

One could say that the main aim of this project is activation. An activation of a return to inner memory, to zones of culture that were never fully legitimized by religion, politics, or morality. This is what makes the work deeply personal and at the same time universal. The Balkans in this performance are not a geography, but a state in which pagan, Christian, bodily, and traumatic elements coexist without destroying one another.

Eroticism here does not seek to be attractive. It is rough, ritualistic, at times almost aggressive, and for that very reason it is devoid of vulgarity. Vulgarity arises where the body is separated from meaning. Here, the body itself is meaning.

It is worth noting that for the contemporary viewer, such scenes may appear excessive or even indecent. But perhaps it is not the scenes that are excessive, but we who have become impoverished. Our culture has learned to fear its own body and labels as obscene everything that exceeds permitted boundaries. In any case, one thing is clear. Abramovic is not trying to shock. She refuses to filter. And in this refusal lies radical honesty and freedom.

Not only in this project, but throughout her entire career, Abramovic presents a body that ceases to be individual. It belongs not to a person, but to a community, to the land, to a cycle. It does not tell the story of a personality. It serves, connects, becomes an instrument of relation. And this is precisely what may be frightening today. The illusion of autonomy disappears, the body ceases to be the property of the I.

In a broader context of performance art, such a dissolution of the individual self into experience is not an exception, but one of its fundamental strategies. The artist’s body ceases to be a carrier of authorial style and becomes a conduit, a channel through which collective fears, traumas, desires, and historical tensions pass. Performance always operates on the edge of loss of control. The artist initiates the process, but does not fully possess it. In this sense, it is closer to ritual than to a work of art in the conventional understanding.

It is no coincidence that other key figures of performance art, such as Joseph Beuys (1921-1986) and Ana Mendieta (1948-1985), among others, also turned to the body as a site of memory and transformation. In Beuys, it was a body wounded by history and myth. In Mendieta, a body merging with the landscape, disappearing into earth, grass, blood. In all these cases, the focus was not on self expression, but on an attempt to restore lost connections between human beings and nature, between the present and a repressed past, between individual experience and the collective unconscious.

A similar turn toward embodied memory and vernacular knowledge can be found in the work of contemporary artists from Russia. For many of them, performance becomes a way to work through questions of identity, forgotten histories, and inherited traditions. The performances of Alice Hualice, for example, draw on folk practices, repeated bodily actions, and personal myths to explore identity as something lived, fragile, and constantly changing. Her work unfolds at the meeting point of the personal and the ancestral, where traditional gestures are brought back to life through the contemporary body, but not as folklore to be preserved. It is rather about lived actions that help the artist explore who she is and where she comes from. In this way, folk culture is treated as a tool rather than a set of symbols, a way for the body to remember and to think.

This approach resonates with a broader lineage of Russian performance art, from the radical investigations of instinct and dehumanization of Oleg Kulik (b.1961), to the endurance-based works exploring vulnerability and collective pressure of Olga Kroytor (b.1986) and Taus Makhacheva’s (b.1983) performative engagement with Dagestani traditions, gravity, and transmission. In each case, the body functions as a site where cultural memory is neither preserved nor represented, but temporarily activated, only to remind us of itself and to be reinterpreted before disappearing again.

Unlike traditional art forms, performance leaves no stable object behind that can be fixed, possessed, or fully contained. Its primary value resides in the immediacy of the encounter: the charged space between the artist’s presence and that of the viewer, experienced in real time and irreducible to repetition. To witness a performance is therefore to accept its urgency — the knowledge that it unfolds only once, and that to be present is essential.

And yet, while the performance itself vanishes, what endures are its residues. Photographs, videos, sketches, and other forms of documentation become the lasting witnesses to an event that can no longer be revisited. These materials do not replace the live act, nor do they claim to stabilize it; rather, they operate as fragments, partial records that attest to something that has already slipped into the past. It is through these documents that performance enters history, not as a fixed object, but as a constellation of traces.

This tension — between the unrepeatable nature of the live act and the persistence of its documentation — is precisely what allows performance to resist full institutionalization and commodification. It does not aspire to wholeness or closure, nor can it be entirely archived or controlled. Like lived experience or bodily memory, it remains incomplete, unstable, and ultimately elusive.

Perhaps this is performance’s greatest strength. In a culture driven by preservation, accumulation, and permanence, performance asserts the value of vulnerability, loss, and temporality. It reminds us that meaning does not always reside in what can be preserved. Some forms of knowledge are transmitted only through presence — through risk, exposure, and the physical encounter itself — even as their traces continue to speak long after the moment has passed.

ABOUT WHAT CANNOT BE COLLECTED

Barcelona, 27th of January 2026

Soviet art is too often reduced to a single visual language of ideology, heroic imagery, and state propaganda. In reality, it encompasses nearly seventy years of radically shifting artistic practices, shaped by changing political conditions, personal strategies of survival, and genuine creative ambition. Today, collectors and scholars increasingly recognize Soviet art not as a monolith, but as a complex ecosystem of official, marginal, and unofficial practices whose diversity is central to its historical and market relevance

Text by Angie Afifi

Soviet art is often perceived as something homogeneous: posters, heroic figures, slogans, and a visual language fully subordinated to ideology. This view is more myth than reality, as it oversimplifies a far more complex picture. When Soviet art is considered more broadly, it becomes clear that propaganda was only one of its functions and only during a specific period. Moreover, the art market clearly shows today that collectors no longer view Soviet art as a single ideological style, but rather as a field of diverse artistic practices, ranging from official painting to informal and experimental movements.

It is important to remember that Soviet art spans an exceptionally long historical period of almost seventy years, from the revolutionary period beginning in 1917 to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. During this time, political conditions, cultural policies, generations of artists, and even the very understanding of what art could be were constantly changing. To speak of Soviet art as a unified phenomenon would therefore mean ignoring its internal diversity and evolution.

The first post-revolutionary decades were marked by radical artistic experimentation. The avant garde of the 1910s through the 1930s, represented by figures such as Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935), Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953), Lyubov Popova (1889-1924), Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956), El Lissitzky (1890-1941), and Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), became not only a part of Soviet culture but also one of the most significant contributions to the history of global modernism. Artists searched for a new visual language for a new society, working with abstraction, geometry, and space, and seeking to merge art with architecture, design, and everyday life. This period deserves a separate and detailed discussion, as its importance extends far beyond the Soviet context. It is essential, however, to emphasize that this very avant garde was later banned and pushed out of official cultural policy.

In the context of the international art market, statistics from public auctions show that this period of Russian and Soviet art remains the most highly valued. This is due to the fact that these works are recognized as major artistic innovations that shaped the course of twentieth century art, combined with the rarity of authentic masterpieces on the market and, as a result, consistently strong auction demand and record prices.

The dramatic history of the Russian and Soviet avant garde also attracts particular attention from modern collectors and investors. By the mid 1930s, the state had established strict control over artistic production. Socialist realism was declared the only acceptable method, while any forms of artistic expression that did not serve ideological objectives were quickly seen as unimportant or even outlawed. Abstraction, formal experimentation, and individual artistic searches were labelled hostile. Many artists were forced to change their style, abandon earlier ideas, or withdraw from public life altogether. From this moment on, a significant part of artistic production effectively became dependent on the state and was required to serve ideology directly, operating within rigid political and aesthetic boundaries presented as serving the common good.

Despite the strict framework of socialist realism, works continued to be created in parallel that appeared, at least on the surface, to focus on everyday life and the individual. Genres such as portraiture, landscape, and genre scenes developed during this time. However, even these forms inevitably carried ideological undertones, glorifying labour, the Soviet individual, and industrial progress, combining realistic technique with the characteristic romanticism and pathos of the era.

Even in the relatively few works that seemed to lack an explicit connection to propaganda, one can clearly detect the imprint of what is often described as safe art. This was art that did not challenge the norms of its time, had no independent manifesto, and was incapable of questioning the ideological foundations of the regime or disrupting the established social order and discipline. This does not mean, however, that all works produced within this framework were devoid of artistic complexity or individual expression; rather, the space for such expression was severely limited and carefully circumscribed.

It was precisely under conditions of strict state control and ideological regulation of artistic life that socialist realism emerged as the official and dominant artistic method in the Soviet Union and other socialist countries. It was presented as the correct and only acceptable way of depicting reality and humanity in accordance with the ideals of the new socialist society. Socialist realism dictated not only themes and subjects but also the methods of artistic expression, subordinating art to the tasks of education, mobilization, and ideological influence. For most of the Soviet period, it remained virtually the only permissible form of public artistic expression.

At the same time, such instrumentalization of art was not unique to the Soviet system. Similar mechanisms existed in other authoritarian and totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century. In Maoist China, art was likewise subordinated to ideological goals and used to shape the image of a new individual. In fascist Germany, artistic production was strictly regulated, and any deviation from the canon was declared degenerate. In Italy under Mussolini, despite relative tolerance toward futurism at an early stage, art gradually became embedded within the state propaganda system. Franco era Spain was no exception, as art existed under conditions of censorship and political control. In all these cases, art functioned as a tool of governance and legitimization of power, allowing no room for self-expression, experimentation, or the search for new ideas and visual languages.

As for socialist realism itself, represented in the earlier decades by artists such as Alexander Laktionov (1910-1972), Dmitry Nalbandyan (1906-1993), Isaac Brodsky (1884-1939), just to name a few, this period of Soviet painting remains relatively underrepresented within the global art canon. The market for socialist realism is indeed a specialised niche yet this does not make it marginal, nor does its appeal rest solely on ideology or nostalgia. For many collectors today, interest is driven by the high level of technical mastery, rigorous academic training, and painterly skill that defined Soviet artistic education. These works are often characterized by clarity of composition, confidence of drawing, and a direct, legible narrative language, qualities that became increasingly rare in later twentieth-century Soviet and post-Soviet art.

It is also essential to look beyond Moscow and Leningrad. Across the Soviet Union, in what are today independent countries such as Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, and the Baltic states, artists were educated within the same demanding system while developing distinct, locally inflected visual languages. Many produced works full of sensitivity and meticulous craftsmanship, combining realist conventions with regional traditions, landscape, and scenes of everyday life. Figures such as Tair Salakhov (1928-2021), Viktor Popkov (1932-1974), Geli Korzhev (1925-2012) complicate the notion of socialist realism as a monolithic or purely celebratory style. Working within the official system, yet often at its expressive limits, these artists introduced degrees of psychological tension, ambiguity, and emotional restraint that resist a purely propagandistic reading. Korzhev, for instance, was neither a dissident nor a conventional establishment figure. His paintings addressed themes of war, power, and historical trauma with restraint and psychological depth, focusing not on heroism but on their impact on the human condition. It is precisely this combination of technical excellence, emotional gravity, and controlled narrative that increasingly resonates with collectors today, allowing socialist realism to be approached not simply as ideology, but as a complex and deeply human artistic language.

Particular attention should also be given to unofficial art, or nonconformism. Despite bans and censorship, from the late 1950s onward an increasing number of artists began working outside official institutions. Figures such as Ilya Kabakov (1933-2023), Eugeni Mikhnov-Voytenko (1932-1988), Vladimir Weisberg (1924-1985), Anatoly Zverev (1931-1986), Vitaly Komar (b.1943) and Alexander Melamid (b.1945) created art which was personal, experimental, sometimes ironic and sometimes tragic. Abstraction, symbolism, and philosophical or existential themes became forms of internal resistance to the system. These works were rarely intended for public display, which is precisely why they are perceived today as particularly authentic.

It is also worth noting that for those seeking to buy Russian art with an investment perspective, nonconformist art represents one of the most attractive segments of Soviet art today. Unlike the avant garde, it remains more accessible and offers a wider price range for both investment and collecting. The investment potential of this field is confirmed by its consistent presence among the top lots of leading auction houses over the past five years, led by artists such as Ilya Kabakov, Oleg Tselkov (1934-2021) Oscar Rabin (1928-2018), Erik Bulatov (1933-2025), and Vladimir Nemukhin (1925-2016).

To conclude, it is important to emphasize that over nearly seventy years of the Soviet Union’s existence, artists interacted with the system in different ways. Some adapted, some compromised, and others sought forms of inner freedom or quiet resistance. This diversity of strategies is what gives Soviet art its depth and complexity. Today, collectors and the art market increasingly view it not as a single ideological phenomenon but as a collection of distinct artistic movements and individual practices, each with its own historical and market value. Understanding the context in which these works were created has become a key factor in their evaluation, the formation of collections, and informed investment decisions.

ABOUT WHAT CANNOT BE COLLECTED

Barcelona, 20th of January 2026

‘Don Quixote’ is one of the most enduring figures of world culture, embodying the eternal tension between idealism and reality. In Russian art, this archetype has acquired particular depth, becoming a symbol of inner resistance, moral choice, and the artist’s struggle for meaning. The exhibition ¡VIVA DON QUIJOTE! situates Genia Chef’s long-term artistic project within this broader cultural and historical continuum.

Text by Angie Afifi

‘Don Quixote’ has exerted an immense influence on world culture, inaugurating the modern novel and shaping the image of a hero torn between a lofty ideal and the stubborn prose of reality. Through the figure of the “Knight of the Sorrowful Countenance,” the work has given us the notion of quixotism as a selfless, sometimes naive struggle for high ideals in defiance of reason, circumstance, and public ridicule. The Russian cultural context is no exception. There, Don Quixote occupies a special place. He has taken deep root in painting, literature, and theatre, transforming into a metaphor for the fate of the Russian individual during complex and dramatic historical periods. One might say that Don Quixote in Russian art is an eternal fighter for ideals, a figure of sacrifice and inner resistance, a symbol of opposition to indifference, cynicism, and falsehood. This image was repeatedly explored by Anatoly Zverev (1931-1986), one of the central figures of the Russian avant-garde, who saw in Don Quixote the archetype of the artist-dreamer, a knight of the brush battling for art against all odds. In a broader artistic field, the Don Quixote motif can also be found in the work of Gely Korzhev (1925-2012), where the theme of moral choice and tragic idealism acquires an almost epic resonance. In twentieth-century literature, this image echoes in the works of Mikhail Bulgakov and Viktor Shklovsky, while in theatre and ballet, in the classical production by Ludwig Minkus, Don Quixote becomes a symbol of undying idealism.

Born in Kazakhstan, and emerging from late soviet nonconformist art circles, today German-Russian painter Genia Chef (b.1954) resides in Berlin. He offers his own vision of Don Quixote, approaching the archetype in an attempt to see in it a reflection of contemporary reality. As the artist himself states in his own manifesto, he calls his artistic position ‘Post-Historicism’. It evolved in the mid 1990s during numerous visits to the Spanish village of Cadaqués where he staged famous characters from Russian history and literature in Spanish landscapes. At its core lies a combination of elements of traditional painting with aesthetic experimentation, and a reinterpretation of historical, mythological, and literary subjects in the form of a new mythology. This is certainly not about reproduction or illustration, but about rethinking and developing a new approach to what have become and can be seen as eternal images. You can see this clearly at play in the exhibition “¡VIVA DON QUIJOTE! A Look Through the Work of Genia Chef,” which has just opened at the MEAM Museum in Barcelona and runs until April 26, 2026.

Chef’s Don Quixote project was conceived from the outset as both a large-scale and long-term artistic statement. It will not be confined to the framework of a single exhibition or a completed series, but will continue to develop as an open process as he strives to create one of the most extensive artistic interpretations of Cervantes’ novel in art history both present and past. The current exhibition includes around forty works, only one part of an already substantial body of work that numbers in the hundreds and continues to grow today.

Castilian, La Mancha’s dry and piercing Spain appears in Genia Chef’s works not as a geographical territory, but as an inner space of tension, wind, and light. It is a Spain of the spirit, a Spain of states of being, in which Don Quixote is born and exists, an image that long ago transcended the literary text to become a universal metaphor for human existence. It is no coincidence that Russian Hispanist and head of the cultural department of the Cervantes Institute in Moscow, Tatiana Pigareva, notes that “Don Quixote is a great book by which one can measure one’s own growth, one’s changes, and invent one’s own interpretation.” Don Quixote cannot be exhausted by a single reading. He returns to us again and again, each time within a new historical, cultural, and personal context.

It is precisely this repeated return to the source, to the primal foundation of the myth, that lies at the heart of Genia Chef’s artistic project, founded by Catalan art collector, advisor and patron Jordi Martínez Rotllan and curated by Cristina Planas de la Rocha. The artist himself reflects on how is is not illustrating Cervantes’ novel, but rereading it in a process through which new scenarios, new meanings, and new imaginaries are emerging. A return to Don Quixote becomes a way of reflecting on the present, on human nature, and on the fate of ideals in a world where reality and dream exist in constant conflict. It reminds me of Vladimir Nabokov who once said, “A book cannot be read. It can only be reread.” If Don Quixote comes to us from our childhood, a childhood perception is only the first step. What remains in memory is the gaunt, awkward Don Quixote and the amusing Sancho Panza on his donkey, yet even here lies the brilliant visual image created by Cervantes: one elongated, almost bodiless, like a spirit of madness or divine illumination, the other earthly, rounded, grounded, bound to matter and corporeality.

Over the centuries, Don Quixote has been perceived in many different ways. He has been seen as a madman and as a saint, as a tragic hero and as a figure reminiscent of Christ, depending on the era and cultural context. Yet the basic idea of the struggle for ideals has remained constant: for good, justice, honor, and nobility. Against this backdrop of centuries of interpretations, Genia Chef’s artistic language emerges as an independent statement, connected less to the tradition of illustration than to personal experience and inner search. Although the space of the Soviet artistic underground laid the foundation for Chef’s career, the artist himself acknowledges that it was only after he emigrated that he developed his own distinctive style. As the exhibition demonstrates, many of his works are monumental and conceptual, encompassing both painting and drawing. Nature occupies a special place in his practice, which the artist calls his direct source of inspiration and a faithful companion. If in the twentieth century humanity consistently moved against nature and its laws, today, according to him, the time has come to return to its significance. That is why he actively uses natural materials in his works, such as tea for toning surfaces, olive sauce, feathers, earth, sand, and small stones. This principle is also preserved in the series presented at the MEAM. In these works about Don Quixote, the very soil of La Mancha, the hero’s homeland, is literally present, its matter and relief forming an essential tactile component of the artworks.

Contemplating these monumental tapestries and canvases, the viewer seems to find themselves in La Mancha without physically entering it. The barren atmosphere, vibrating warm tones, and multilayered textures create an explosive, emotionally charged effect. The dramaturgy is built on the juxtaposition and layering of numerous materials, forming a space in which Don Quixote and Sancho Panza unfold as living, relevant images. This materiality invites the viewer to immerse themselves in the work and feel like part of it, accompanying the heroes and living through their adventures together, whether journeys or, of course, the battle with the windmills.

It is precisely through this interaction with Chef’s works that the impulses underlying the myth of Don Quixote awaken in the viewer: the struggle for a higher idea, for one’s own ideals, the search for justice and meaning. Don Quixote here becomes not a character of the past, but a metaphor of the present, a reflection of the inner state of a person who continues to defend their values in a world of doubt and compromise. Ultimately, Don Quixote is a mirror in which everyone recognizes their own windmills and their own struggle.

Today, perhaps more than ever: ¡VIVA DON QUIJOTE!

ABOUT WHAT CANNOT BE COLLECTED

London, 13th of January 2026

St. Petersburg has long been imagined as more than a capital city: it is a blueprint for how power, morality, and knowledge might be built into stone, streets, and bodies. This text explores two rare Catherine-era books that reveal how medicine, urban planning, and Enlightenment ideology converged in Petersburg, turning both the city and its inhabitants into objects of rational design.

Text by Angie Afifi

In the late eighteenth century, St. Petersburg stood as one of the most ambitious experiments in human reason ever attempted. Conceived by Peter the Great as a “window to Europe,” it became under Catherine II not merely an imperial capital but a laboratory of Enlightenment ideals — a city designed to tame nature, refine manners, and rationalize the human soul. If Paris gave the Enlightenment its language, St. Petersburg gave it architecture: geometry turned into government, symmetry into social order. It was a place where science and morality were no longer private pursuits but instruments of empire, where the city itself was meant to educate its inhabitants.

Two rare books from the late Catherinean period — Dr. Andrei Bakherecht’s ‘On the Immoderation of Lust and the Diseases Arising Therefrom’ (1780) and Johann Gottlieb Georgi’s ‘Description de la ville de St. Pétersbourg’ (1793) illuminate this extraordinary moment when medicine, morality, and urban form converged into a single Enlightenment project. These books trace the intellectual anatomy of Catherine’s St. Petersburg — a city where vice was pathologized, virtue quantified, and architecture embodied the principles of reason.

Notably, by the 1770s, Catherine II’s reforms had turned science into statecraft. Physicians, naturalists, and educators were enlisted to serve the moral improvement of the population. The Russian Enlightenment was pragmatic: it sought enlightened order. The Empress admired Voltaire, corresponded with Diderot, founded the Free Economic Society and the Imperial Academy of Sciences. But unlike her French counterparts, she ruled a society still half-feudal, half-frozen in the past. Rationality here required translation into discipline. Science was moral instruction in disguise. A good example of this is Dr. Andrei Bakherecht’s 1780 treatise, printed at the Free Press of Weitbrecht and Schnor, one of the few private presses licensed under Catherine’s cautiously liberal policies. The book’s title — ‘On the Immoderation of Lust and the Diseases Arising Therefrom’ — sounds almost medieval, yet its argument is strikingly modern. Bakherecht writes not as a confessor but as a physician; his goal is not to condemn sin but to classify it. Excessive sensuality, he insists, is a physiological disorder that weakens the body, corrupts the mind, and destabilizes the household — a threat to both individual health and social order.

In other words, the regulation of the body became a means of regulating society itself. In this sense, Bakherecht’s rhetoric mirrors the broader Enlightenment conviction that moral reform could be achieved through scientific vocabulary. The book blends clinical observation with moral urgency: the body is a civic instrument, and indulgence in pleasure a kind of rebellion against reason. By diagnosing lust, he was diagnosing Russia’s own struggle between impulse and order, between nature and civilization. That is why this volume is remarkable. Very few medical-moral tracts from the Russian Enlightenment have survived outside institutional archives, and even fewer were printed in private presses rather than state-controlled ones. The Free Press of Weitbrecht and Schnor operated on the fine line between censorship and freedom, serving a readership of physicians, civil servants, and enlightened nobles hungry for “useful knowledge.” Bakherecht’s treatise thus represents both an artifact of scientific culture and a gesture of intellectual daring — a physician attempting to domesticate desire through the tools of Enlightenment reason.

In turn, Johann Gottlieb Georgi’s ‘Description de la ville de St. Pétersbourg’ (1793), published in Saint Petersburg by Jean Zacharias Logan, offered European readers a detailed and panoramic vision of a city that embodied the Enlightenment’s ideals in its architecture, canals, and street plan.

Georgi, a German naturalist and geographer who had accompanied academic expeditions across Russia, approached St. Petersburg as a taxonomist of civilization. His descriptions are precise, almost architectural in their syntax: the alignment of streets, the measurement of façades, the classification of institutions. For Georgi, St. Petersburg was not merely a city but a living diagram of rational order. Its canals imitated Amsterdam, its avenues Paris, but its spirit was uniquely imperial, attempting to bring order, rationality, and grandeur to social life through urban design. His Description situates the city within the natural sciences as much as urban planning: he writes of climate, soil, and hygiene alongside theaters, academies, and churches, treating them as parts of one ecosystem of civilization. This holistic approach shows that the Enlightenment understood the city as a mechanism for cultivating virtue.

Georgi’s copy, annotated by Alexander Benois (1870-1960), adds yet another layer of significance, connecting the eighteenth-century vision of the city with the perspective of a twentieth-century artist and historian. Benois, one of the founders of the World of Art movement, was obsessed with St. Petersburg as both myth and moral warning. His marginal notes — terse, emotional, sometimes ironic — transform Georgi’s Enlightenment optimism into historical irony. Where Georgi saw a city of reason, Benois saw the shadow of autocracy. His handwriting in the margins turns the eighteenth-century text into a palimpsest of two eras: one constructing order, the other mourning its collapse. The very fact that this Enlightenment description passed through Benois’s hands testifies to its afterlife as a symbol of the Petersburg myth — the dream of a rational utopia forever threatened by its own perfectionism.

Both Bakherecht and Georgi, in different registers, reflect the moral ambition of Catherine’s project, a kind of social architecture. The city, the body, and the soul were to be governed by the same principles: balance, moderation, and symmetry. Doctors were moralists, architects were legislators, and the Empress herself fancied the role of philosopher-queen. In this sense, the two books can be seen as complementary parts of a single intellectual system. Bakherecht seeks to discipline the private passions that threaten public health; Georgi describes the public order designed to contain those passions. The body and the city mirror one another — both striving toward equilibrium.

What makes these books so precious today is not only their rarity but the world they reconstruct. They belong to a brief and fragile moment when Russian modernity still believed in coherence. Within a generation, Napoleon’s wars, censorship, and romantic nationalism would dissolve the rational optimism they represent. Bakherecht’s moral medicine would give way to 19th-century psychology and moralism; Georgi’s geometrical city would turn into Dostoevsky’s fevered labyrinth. Yet in these volumes one still hears the confident voice of Enlightenment: the conviction that knowledge could purify, that design could redeem, that human beings could be perfected through the ordering of space and desire.

There is also a subtler irony. The Enlightenment that sought to discipline pleasure and regulate behavior also created the modern idea of individuality. By classifying human impulses, thinkers like Bakherecht gave them visibility; by mapping cities as systems, observers like Georgi revealed their underlying tensions. Both books, in their scientific clarity, inadvertently preserve the very irrationality they sought to suppress. Reading Bakherecht’s warnings against lust, one senses the fascination beneath the condemnation; reading Georgi’s plans for urban harmony, one glimpses the anxiety of control.

Together, these volumes illuminate the paradox at the heart of Enlightenment modernity — the conviction that reason could redeem chaos. They show how Catherine’s St. Petersburg was less a city than an argument: that civilization could be built from symmetry, that morality could be engineered, that desire itself could be measured and reformed. Yet in their pages, as in the city they describe, order and obsession blur into one another. The doctor who diagnoses lust and the geographer who maps perfection share the same faith — that knowledge can save us from ourselves. The Enlightenment’s desire to measure everything reveals, in retrospect, a deeply human desire to understand, order, and make sense of the world. Catherine’s Petersburg, gleaming on its marshes, endures as their monument: at once sublime and fragile, forever constructing enlightenment.

ABOUT WHAT CANNOT BE COLLECTED

.jpeg/:/cr=t:0%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:100%25/rs=w:400,cg:true)

London, 23rd of December 2025

A landmark November auction in New York once again demonstrated the power of the art market to redefine artistic value in a matter of minutes. At its centre stood the large painting El sueño (La cama) by Frida Kahlo, whose sale set multiple records and reignited debate around myth, scarcity, and the global positioning of Latin American art. Young cuban artist and writer Giselle Lucia Navarro writes about her impressions of this monumental event which has sent ripples through the Latin American art scene from Mexico City to Havana.

Text by Giselle Lucía Navarro

Once again, winter turned New York into a highly anticipated rendezvous for the art world. Heightened expectations and close attention to legendary art collections brought the great Surrealist masters again into the spotlight. In ‘Exquisite Corpus’ auction at Sotheby’s exhibited in a darkened space in the fabled Breuer building, were works by Salvador Dalí, René Magritte and Max Ernst as well as Frida Kahlo who in her lifetime did not consider herself part of the movement. Two dozen works offered for sale all wrapped up and marketed in the bottle of Surrealist art.

It is always intriguing to observe the destiny that awaits a work of art once it leaves the artist’s studio. Until that moment, it seems protected by the aura of its creator; upon departure, it comes of age. Its fate differs depending on whether it survives in institutional or private collections. At times, circumstances cause works to literally vanish for many years, only to reappear later in an auction room and be sold again to a new owner. Ultimately, the value of a work is always shaped by speculation and context: it is born of a historical moment and continues to be moulded by the circumstances through which it survives.

The most significant moment (or four minutes) in the auction was the sale of El sueño (La cama) by Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. The bidding gathered extraordinary momentum until it eventually reached $54.7 million dollars, a midpoint within Sotheby’s presale estimates, yet one that set three records in a single night: it became the most expensive work ever sold by the artist herself, the highest price achieved for a work by a woman at auction, and the highest sum paid for a work by a Latin American artist.

Who would pay such a sum for a work by Frida Kahlo? Who might have the privilege of contemplating that intimate dialogue with death from the living room of their home several times a day? In just four minutes, the destiny of the work was decided. The bidding was led by Anna Di Stasi, Head of Latin American Art at Sotheby’s, acting on behalf of a collector on the telephone whose identity still remains anonymous.

What is it about this painting that makes people desire ownership of it? Certainly, a powerful myth surrounds the figure of Frida, who, beyond becoming a pop icon of Mexican culture, is an artist deeply admired all over the world. Her life was brief and turbulent, tragically cut short at the age of 47 in 1954. A Mexican woman, the wife of Diego Rivera, she lived in a time and environment rich in cultural influences, with a personality that was both avant-garde and exotic for her era. After a serious accident in her youth and a bout of polio, her existence became a painful poem that nonetheless inspired the creation of just over one hundred paintings, a third of which are portraits in which she frequently appears.

Beyond these considerations, and beyond the fact that very few of her works are available on the international market—particularly since the Mexican government declared her work national patrimony and prohibited the export of her paintings outside Mexico—there is in Frida’s canvases a visceral, autobiographical quality that allows viewers to connect with her. It is as if Kahlo possesses those who look at her brushstrokes from some other unknown dimension, or perhaps from that very one into which she allowed us to peer through her paintings.

El sueño (La cama) auctioned by Sotheby’s, nearly three feet wide, is large in format when compared to her usual output. She painted this self-portrait after a trip to Paris in 1940, a year that marked Frida’s life through physical suffering and the emotional chaos of a divorce. It depicts the artist in a dreamlike state: her body lies on a four-poster bed, above which rests a papier-mâché skeleton. This figure, known in Mexico as a Judas, carries a bouquet of flowers on its chest and a series of firecrackers tied to its legs. According to some scholars, the painting’s symbolic value demonstrates the artist’s iconographic connection to Mexican cultural tradition and to the central themes of her work.

The painting, which had not been exhibited since 1999, had previously been sold at Sotheby’s in 1980, when it was purchased by a Turkish-American producer for $51,000 dollars. The phenomenon behind the dramatic increase in its value over the past 45 years is also linked to the limited availability of such works on the market, which prevents rapid saturation.

The record set this November in New York will likely be followed by further sales of Kahlo’s paintings despite their rarity. It is nearly predictable that other collectors will, in time, decide to test their luck with their works, whether or not they reach astronomical figures. The art collector always assumes the risk of investment in an uncertain future.

There may be no other Latin American artist around whom so much mysticism persists as that which surrounds the image of Frida Kahlo—or perhaps we simply have not yet had time to see other such myths take shape?

Beyond the hype of fashions and current trends, beyond whether we like a work in question or not, what this event makes clear is that Latin American art continues to be increasingly visible in major auction houses and on the international market, undergoing a constant and growing revaluation. This includes the prominence of female figures such as Frida Kahlo, Leonora Carrington and Tarsila do Amaral, which somewhat decentralises the market’s focus and drives demand for these artists within the circuits of fairs, auctions and biennials—alongside significant names such as Diego Rivera and Wifredo Lam.

For younger generations of artists in the region, like myself, events of this kind represent the consolidation of a shift and a change in perspective towards the work of both established and emerging artists, and above all towards the preservation and dissemination across the world of our Latin American artistic heritage.

ABOUT WHAT CANNOT BE COLLECTED

London, 29th of November 2025

With the famous Fabergé Winter Egg going under the hammer at Christie’s in London, young, independent art historian Angie Afifi reflects on the never-ending endure of the firm’s striking and much treasured objets d’art and reaffirms their relevance today explaining their current popularity around the world.

Text by Angie Afifi

The story of Fabergé has been often distilled into a single crystalline and quintessential symbol of genius: the Winter Egg of 1913. It was a triumph of both imagination as well as technical daring, qualities that lie at the heart of Fabergé’s success. Conceived as an Easter gift from Emperor Nicholas II to his mother, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, the piece has twice broken the world auction record for a work by Fabergé and now reappears at the upcoming Christie’s sale with high expectations as the hero piece in the Important Works by Fabergé from a Princely Collection.

The return of the Winter Egg to the auction block in London both reminds us once again of the egg’s legendary status and affirms the continued vitality and relevance of the market for Imperial Russian works of art. The Winter Egg, with its rock crystal carved as thin as glass and studded with platinum and diamonds to resemble frost, remains a testament to the spellbinding audacity of Russian artistry. Carved from an exceptionally clear ovoid of rock crystal, its surface is engraved with frost patterns so weightless that they seem to have been breathed onto the crystal rather than cut into it. Snowflake motifs in platinum, each set with rose cut diamonds, shimmer like morning frost catching pale sunlight hinting at approaching Spring. Even the base, also carved from rock crystal, evokes thawing ice, introducing a counterpoint that transforms the egg into a miniature meditation on the profound shift of the season in Russia the promise of Spring after a long cold winter. And when opened, the egg reveals its celebrated surprise, a bouquet of spring flowers carved from delicate hardstones and set in a crystal basket edged with diamonds. It is a simple, yet poetic and christian marriage of winter’s glacial exterior and spring’s promise hiding within.

However, to truly understand the enduring obsession with Fabergé, you can also look beyond the famous Imperial Easter Eggs to the many other objects that lived and breathed in the daily rhythms of the Russian and European aristocracy, such as the table clocks and photograph frames that initially adorned the desks of St Petersburg’s elite before Fabergé’s fame spread abroad. It is within these functional and exquisite objects de vertu that the real breadth, productivity and industryof the firm is revealed, fueling then and now a global market that is currently experiencing a mini boom, among collectorsfrom New York to Qatar and back. The designer of the Winter Egg, possibly one of the most inventive of all the eggs,Alma Pihl, serves as a vital entry point into the narrative about the sheer originality of Fabergé’s creative output. As a female artisan in a male dominated industry, Pihl broke away from the heavy Neoclassical and Rococo styles that defined the period. She looked with authentic, fresh eyes at frost on a windowpane and transformed it into a sophisticated and beautiful work of art. Her innovation is central to understanding Fabergé’s value today, for the firm can not be defined solely by material opulence, but by an intellectual and creative approach to aesthetics. Pihl’s legacy reminds us that Fabergé was a house of designers as much as goldsmiths.

This same spirit of distinctive, masterful design is evident in the pieces Vickery Art is currently offering for sale in an exclusive collection of Russian Works of Art and Fabergé from a private European collector. Among the many highlights is a rare salmon pink triple photograph frame. Crafted by head workmaster Mikhail Perchin, the frame is a triumph of the enameler’s art. Its fan shaped, demi lune silhouette is instantly recognisable and echoes the design language of similar examples preserved in the Royal Collection of H.R.H. King Charles III. The guilloché enamel is rendered in a deeply saturated, translucent salmon pink, a colour notoriously difficult to fire without scorching. Laid over a sunray ground, it produces a dynamic optical effect in which light seems to pulse upward through the enamel. The frame celebrates memory, elevated by green and rose gold mounts formed as ribbon tied laurel leaves. The presence of three oval apertures suggests a piece intended for a parent or spouse, an intimate object designed to hold the likenesses of loved ones.

While photograph frames capture memories, Fabergé clocks capture time, and the market for these timepieces has proven to be one of the most resilient and active sectors in the field. The mechanical complexity combined with the artistic casing makes them dual-natured treasures. A prime example of this is the two-colored gold and enamel desk clock by workmaster Victor Aarne. Also taking a demi-lune form, this piece utilizes a translucent mauve enamel over an undulating sunburst ground. The choice of mauve, a favorite color of the French Ancien Régime and the Romanov court, evokes a sense of regal nostalgia. Aarne’s work is characterized by a specific crispness in the gold chasing, seen here in the reeds and ribbon-tied staffs that border the dial. The way the gold flourishes interact with the purple enamel creates a contrast of warmth and coolness that is visually arresting.

The diversity of Fabergé’s design language is further illustrated by the triangular silver and enamel desk clock, another work by Mikhail Perchin. Departing from the soft curves of the demi-lune, this piece embraces a sharp, architectural geometry. The pale blue guilloché enamel serves as a backdrop for applied Neoclassical motifs, including anthemia and floral designs reminiscent of Greek and Roman architecture. This clock represents the "Intellectual Fabergé", restrained, elegant, and historically aware, and speaks to the collector who values scholarly craftsmanship and the refined adaptation of classical vocabulary into modern luxury. The triangular shape is popular among collectors.

Completing this study of time is a rectangular silver-mounted clock by Henrik Wigström. This piece signals a shift toward a more pared back, modern aesthetic, with alternating narrow and wide vertical bands in mauve enamel that create a rhythm almost contemporary in its clarity. What makes the clock particularly compelling from a market-historical perspective is its use of 91 zolotniki silver. This higher standard of purity (94.79 percent) indicates that the object was likely produced specifically for the London market to meet British sterling expectations. This detail underscores Fabergé’s early self-conception as an international brand, a global orientation that has expanded exponentially today as demand for Fabergé clocks and frames continues to surge in emerging markets across Asia and the Middle East.

Why is this market booming now? In periods of economic and political instability and uncertainty such as ours, tangible assets with established provenance and a longsstanding market tend to perform as safe havens. Yet unlike gold bars or raw diamonds, as an alternative asset, a Fabergé clock offers a “triple value”: intrinsic material worth, artistic scarcity and it is something that you can display in your home and enjoy. It has international appeal, the Fabergé brand is known all over the world. Collectors in the Middle East appreciate the intricate geometrial designs of guilloché enamelling, which resonates with the region’s own longstanding traditions of mathematical ornament. At the same time, American collectors continue to drive prices upward for works with Imperial associations, touched by the Romance and drama of the finale to the Romanov rule. Diaspora Russians living across the world are buying into their own pre-revolutionary heritage; European collectors have a natural connection with Fabergé’s aesthetics. And Asian collectors have a natural love of objects with cultural and historical associations, not to mention the obvious similarities between Fabergé’s hard stone animals and netsuke figures.

However, it is provenance that perhaps remains the single most powerful multiplier in the valuation of the Russian decorative arts. While the market for traditional Fabergé objects is consistently strong, a confirmed link to the Romanovs transforms this interest into greater desire. Objects once owned by members of the Imperial family are approached not simply as antiques but as relics of a world that vanished abruptly and violently. This historical charge adds a dimension of value, the tragedy of the Romanovs, juxtaposed with the splendour of their court, forms an emotional catalyst: to acquire a Wigström clock or a Perchin frame with Imperial provenance is to secure, however briefly, a fragment of the soul of the Winter Palace.

Furthermore, the golden age of Fabergé scholarship over the past three decades has also helped fuel this fire. As more archives are digitized and more exhibitions are mounted, the appreciation for specific workmasters, such as Aarne, Perchin, and Wigström, has deepened and broadened with collectors seeking out the distinctive characteristics of these artisans. This sophistication in the buyer pool has created a robust, competitive market, enhancing the appeal of these objects. This allure ultimately lies in their exceptional condition, unique forms, and, of course, in their ability to transcend their function. Even as new generations of collectors enter the arena, the appetite for these masterpieces shows no sign of satiation.

Although the iconic Winter Egg at Christie’s has deservedly grabbed the headlines, it is the clocks, frames, cigarette casesand lighters, all the daily companions of the Tsars and their circle that sustain the market at large. They remain, as they were over a century ago, the powerful symbols of taste, history, and enduring luxury.

ABOUT WHAT CANNOT BE COLLECTED

Barcelona, 22nd of November 2025

As the market for Surrealist art continues to surge, with works by Dalí and his contemporaries attracting intense global demand, it is worth asking how much of this value rests not only on the art itself but on the myth of the artist. Salvador Dalí understood earlier than most that to prosper in such a landscape, genius had to be staged, packaged and relentlessly marketed—turning the artist into the most powerful brand of all.

By Angie Afifi

Long before the phrase ‘personal brand’ entered our cultural vocabulary, Salvador Dalí understood that genius could be sold, packaged, and performed. He understood that he was not merely an artist but also a living experiment in marketing. Observing Dalí in public life meant seeing a person who consistently shaped his own public identity with deliberate intention. Every action and controversy was planned to attract attention and strengthen his long term visibility. He demonstrated that an artist’s public persona can influence audiences as strongly as the artworks themselves, significantly affecting an artist’s cultural and commercial impact.

As a youth Dali wore velvet jackets and lace collars, cultivating eccentricity like a weapon, and learned that if he acted insane with enough conviction, people eventually would call it genius. He discovered early the rule that would define his life: art may require talent, but fame demands theatre. For Dalí, identity wasn't just a medium; it was as rich and vital as oil paint itself. Long before the digital age made self-promotion a career necessity, he intuitively grasped the magnetism of spectacle, understanding that anticipation could be sculpted into an artwork. His instantly recognizable moustache, waxed into sharpened points, became his corporate logo; his eyes, widened with calculated mania, served as the advertisement for his own crafted mythology. He flawlessly executed the role of both product and pitchman, establishing the essential template for the artist as brand that defines the twenty-first century.

Dalí’s real revolution was the way he treated marketing as part of his creative process. While many artists tried to protect the purity of their work from commercial influence, Dalí openly integrated commercial success and public promotion into his artistic practice. He adapted his work to public demand, whether producing luxury items or mass reproductions, challenging the traditional separation between high art and commerce. One notable example occurred in 1939, when the department store Bonwit Teller invited him to design a window display. He filled it with taxidermied animals, bleeding mannequins and a black satin bathtub. When the store protested, he smashed the glass and was arrested. The next day, photographs of the incident appeared in newspapers across New York. Dalí understood what many artists still resist: in an age obsessed with spectacle, scandal itself could serve as publicity. Moreover, Dalí collaborated on a wide range of endeavors that combined artistic creativity with commercial purpose. He designed jewelry, furniture, perfume bottles, and even the Chupa Chups logo, which he sketched in under an hour on a café napkin. He treated this aspect of his career as an extension of his artistic practice, skillfully using the symbiosis between his artworks and commercial ventures to keep his distinctive style and controversial persona highly visible.

The careful cultivation of his image and the integration of commercial strategy into his work help explain why Dalí’s influence persists not only culturally but also financially. According to Artprice data for 2025, Dalí’s ranks eighty-eighth in global auction sales volume and remains one of the most liquid artists of the twentieth century. More than fifty-eight thousand auction results are recorded under his name, with drawings and watercolours leading the category, while prints make up a substantial share of the global supply. His strongest results appear in the United Kingdom, with consistent demand in the United States, France, and Spain, alongside growing activity in China and Japan.

In the wider context of Surrealism, these trends are even more pronounced. New York and London continue to dominate the segment, as shown by the record sale of René Magritte’s L’empire des Lumières at Christie’s in 2024 for over $121 million, along with strong performances by Max Ernst and Joan Miró, whose works consistently occupy the upper price range of the movement. Regular thematic auctions such as Surrealism and Its Legacy at Sotheby’s, combined with active European and Asian markets, create a stable global environment in which Dalí serves as a key point of reference, connecting the highly liquid graphic segment with top-tier painterly and museum-level Surrealism.

The strength of this market presence underscores what made Dalí’s brand so powerful. Beneath the self-parody and flamboyance lay an artist of intense, almost maniacal discipline. He called his process the paranoiac-critical method, a system for harnessing irrationality through deliberate logic. While many believe Dalí’s madness was pure chaos, in reality it was carefully calculated. This paradox, insanity crafted with mathematical intention, became the heart of his brand. Dalí understood that the modern public wanted its geniuses to be half divine and half absurd. They wanted contradictions they could debate and figures too strange to ignore, so he supplied exactly that. When asked about his politics, he described himself as an anarchic monarchist, a deliberately impossible phrase that delighted him for its theatrical incoherence. Every insult, every accusation of narcissism or fraud, merely reinforced his myth.